The alluring aroma of wood-fired pizza wafts from Flatbread Company. Gulls swoop and cry overhead, while foot-stomping fiddle notes emanate from Rí Rá Irish Pub & Restaurant.

The alluring aroma of wood-fired pizza wafts from Flatbread Company. Gulls swoop and cry overhead, while foot-stomping fiddle notes emanate from Rí Rá Irish Pub & Restaurant.

Horns blast from ferries at Casco Bay Lines as passengers set sail for island homes and harbor tours.

A mixed-use working waterfront, this is Commercial Street – Portland’s gateway to the world.

It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974 and named one of America’s Top 10 Great Streets by the American Planning Association in 2008.

Commercial Street supports Maine’s tourism industry with eclectic retail shops, fine dining, live music, and guided tours.

This is a place of convergence where worlds collide. Office workers grab lunch with colleagues, lobstermen haul cages of crustaceans, and local buskers strum cover songs next to their open guitar cases.

On weekend nights, bachelorette parties amicably wander from bar to bar, wearing matching outfits — sparkly sashes, plastic tiaras, witty t-shirts.

Tourists from across the globe arrive on cruise ships. Runners, bikers, and dog walkers utilize the waterfront trail that connects to Portland’s East End.

And, amid all the bustle of present-day life, if you look a little closer, you can see fragments of the past lingering in Commercial’s stately brick buildings.

Photo: Emma Joyce

Working Waterfront

Commercial Street used to be water. In 1852, a series of wharves off of Fore Street were connected, and a road was formed using fill, most of which came from Munjoy Hill.

With direct access to the sea, this street became a hub for maritime industry and trade.

Trains first arrived in the city with the Portland, Saco & Portsmouth Railway in 1842, which traveled down to Scarborough, Saco, and North Berwick before connecting with the Boston and Maine. This was followed by the northbound train to Canada, initially known as the Atlantic and St. Lawrence Railroad and then taken over by the Grand Trunk Railway, which began operating in 1853 and traversed Commercial.

Although the Grand Trunk’s station complex on Fore Street was demolished in the 1960s, an outbuilding on the corner of India Street and Commercial still stands and is now occupied by Gorham Savings Bank.

Photo: Emma Joyce

Since Commercial Street’s creation, the city has navigated issues pertaining to what can be built and by whom, as civic leaders seek to satisfy both private and public interests. In the 1970s and ’80s a slew of development projects not connected to the working waterfront led to a five-year halt in non-marine construction.

The marine industry is now focused on what’s internationally known as the blue economy – the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth and improved livelihoods and jobs, while preserving the health of marine and coastal ecosystems. The New England Ocean Cluster hosts an annual Walk the Working Waterfront event along Commercial Street, which allows the public to learn more about marine resources from places like the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, Harbor Fish Market, and Bristol Seafood. Participants can explore piers, talk with lobstermen, sample chowder, peek inside a shipping container, or tour a U.S. Coast Guard boat.

Photo: Emma Joyce

Resurgam Resilience

The phoenix, a mythological being that rises from the ashes, has long been associated with Portland as well as the motto Resurgam, Latin for “I shall rise again.”

On July 4, 1866, two boys playing with firecrackers in a boatyard on Commercial Street (located at the present-day site of Hobson’s Landing condos, formerly Deering Lumber) created sparks that rapidly ignited and spread from building to building. The Great Conflagration left more than 10,000 people homeless, decimated manufacturing companies, and consumed one third of the city.

Nevertheless, Portlanders carried on. The fire in 1866 wasn’t the first time that the city had seen destruction. Homes, businesses, and lives were taken in wars with France in the 1600s and again by a British naval bombardment in 1775.

In addition to resources offered through official tour companies, you can learn about Portland’s waterfront history through self-guided walks.

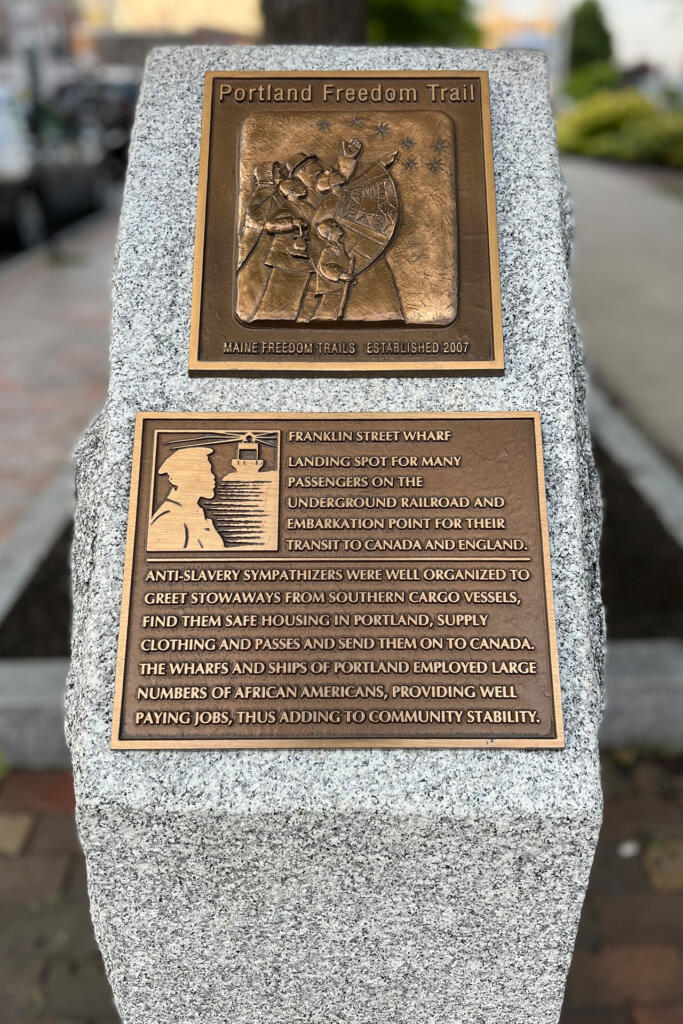

At Franklin and Commercial, the Portland Freedom Trail’s white granite marker commemorates Mainers who assisted African Americans in their journey to freedom through the Underground Railroad. In one documented event in 1857, a runaway slave stowed away on the Albion Cooper, which was bringing lumber from Georgia. He then continued on to Canada with the help of Portland’s anti-slavery supporters.

Photo: Emma Joyce

Planetary Perspective

If you look at images from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, entire galaxies appear as specks in a vast universe. Within those galaxies are solar systems and within those solar systems are planets and on those planets is the potential for life.

When viewed in the context of space, one city street might seem insignificant.

But places like Commercial Street serve as microcosms of human life – examples of the ever-present challenge and opportunity of balancing our built and natural worlds.

Taking into context all that the city has undergone, it’s helpful to know that grit and determination can guide community members in responding to ongoing and future challenges – like the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, and rising sea levels as the climate warms.

At times this place has been bombed, burned, shuttered, and abandoned. Yet, visitors keep arriving. Merchants find new ways of reaching customers. Despite every setback, the people who live here continue to rebuild.

So, whether you’re chatting with locals over a plate of eggs and bacon at Becky’s Diner, sipping on libations at Three Dollar Deweys, or sampling a seafood platter at the floating restaurant, DiMillo’s On The Water, take a few moments to think about the meaning and significance of this special street by the sea.

By Emma Joyce

Photo: Emma Joyce

References/Further Reading

Walking Through History: Portland, Maine on Foot by Paul J. Ledman (book)

Images of America: Portland by Frank H. Sleeper, From the Maine Preservation Commission and Others (book)